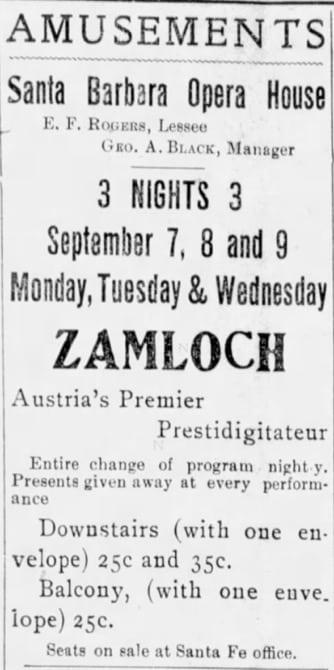

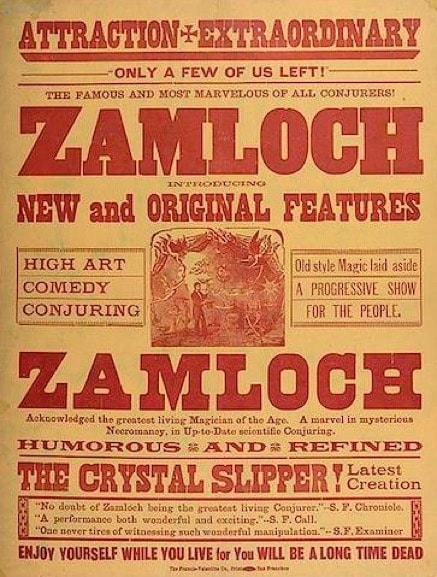

On the night of September 7, 1903, the Lobero Opera House curtain rose and a Santa Barbara audience was introduced to Zamloch the Great, immodestly promoted as “The Wonder Worker of the World.”

Magic was hugely popular in the United States at the turn of the 20th century, and so too was interest in spiritualism – the idea that it was possible to communicate with the dead. The marketing genius of touring magicians like Zamloch was combining sleight of hand magic with spiritualist tricks like spirit table-rapping.

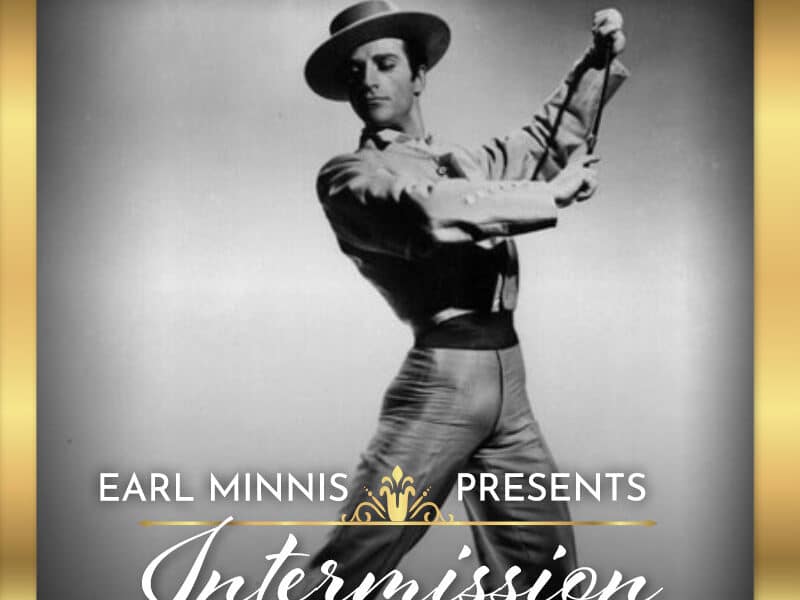

Anton Francis Von Zamloch was born in Austria in 1849 and joined a traveling circus when he was 14 years old. After emigrating to the United States, he began his magic career and found a successful niche performing in western mining towns like Silver City, Nevada, and Tombstone, Arizona. Arriving in a town, he typically paid a visit to the local newspaper office, where he would ensure free publicity by entertaining reporters with his conjuring tricks. According to one newspaper clipping, at one office he made three unopened quarts of whiskey and a large box of cigars vanish, at which point the newspaper editors accused him of banditry and he was nearly shot.

In the late 1800s magicians like Zamloch capitalized on the public’s interest in spiritualism. One of Zamloch’s trademark routines involved his spirit-rapping table and goblin drum, which allowed audience members to ask questions and supposedly receive answers from the spirit world. While some audience members obviously understood stage acts like spirit-rapping to be pure entertainment, large numbers of the audience certainly saw them as proof that communication with the dead was indeed possible.

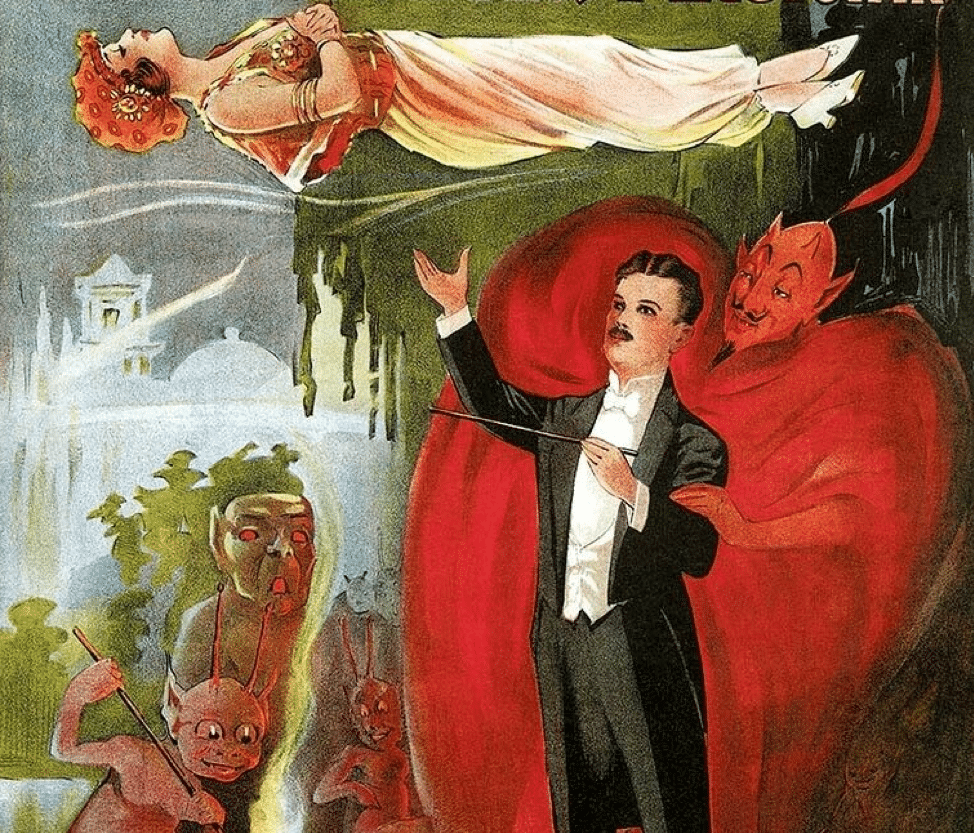

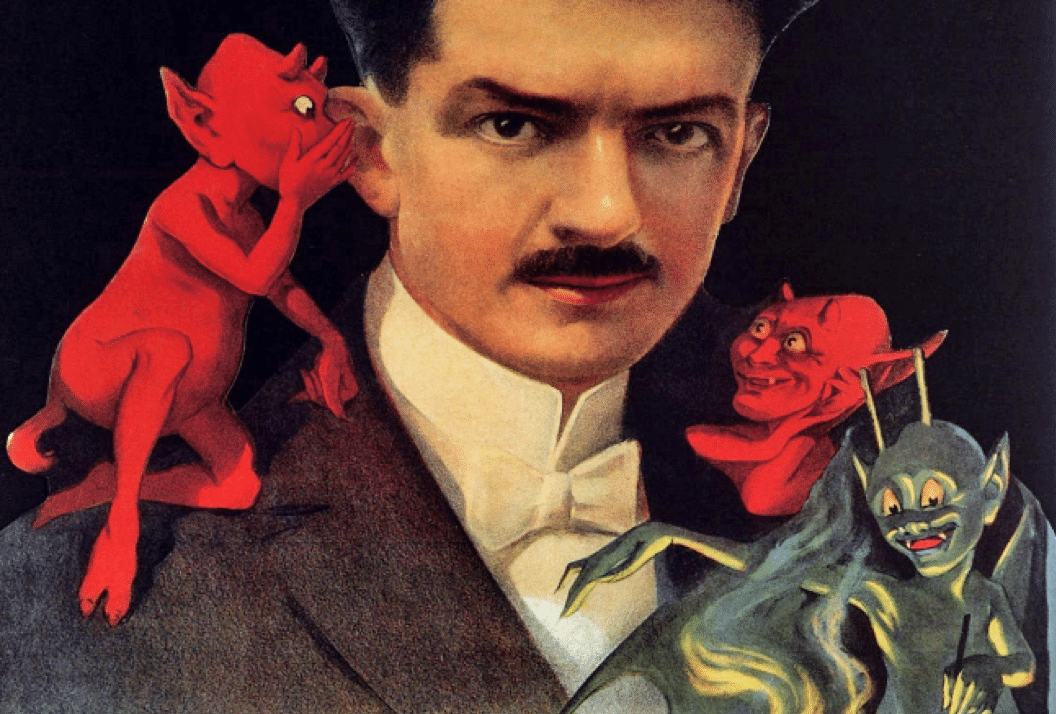

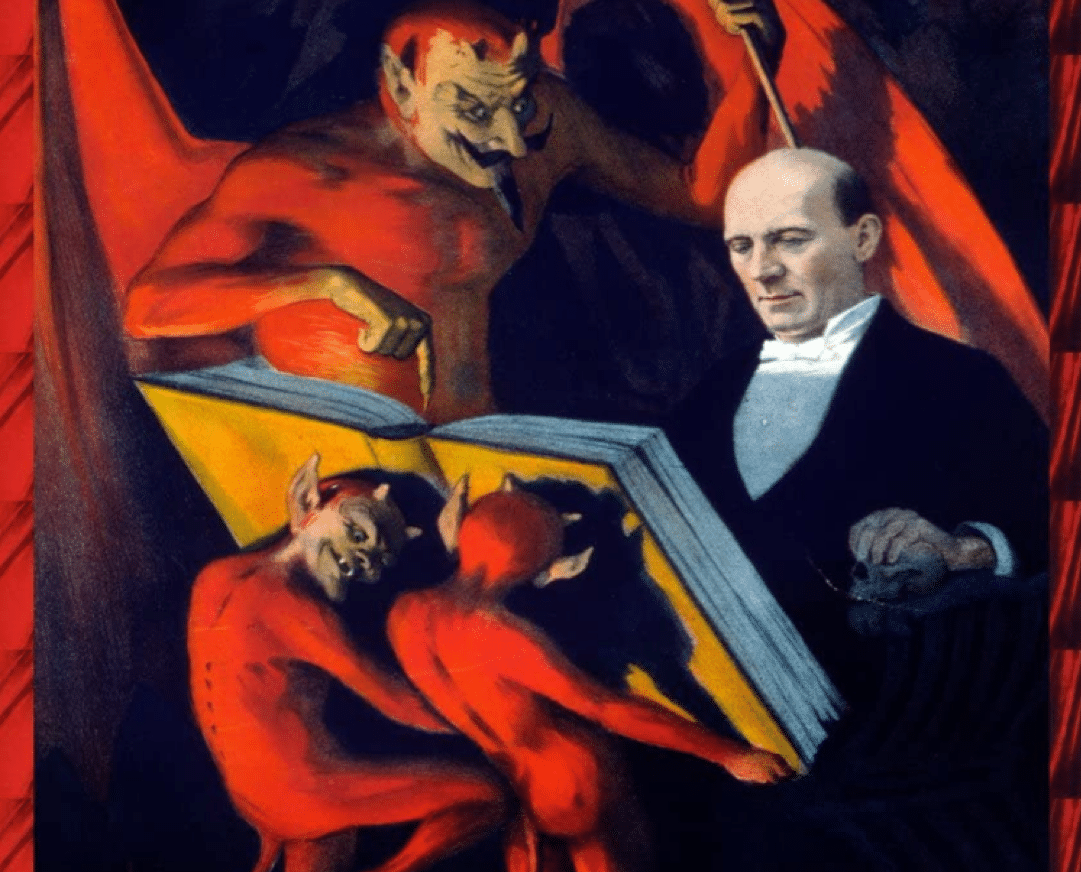

Magicians at the turn of the 20h century gleefully exploited this overlapping of magic and the other-worldly. A favorite theme of advertising posters at the time showed devilish red imps whispering dark secrets into the magician’s ear. The implication – not always tongue-in-cheek – was that only through a pact with the devil were these astounding acts possible.

The Oakland Tribune wrote about a Zamloch performance, “His extravaganzas of magic were so swiftly executed and so mysteriously subtle that two centuries ago he could have been richly deserved being burned at the stake as a necromancer of the blackest arts and a disciple of his satanic majesty.”

Santa Barbara audiences loved Zamloch, and he appeared at the Lobero for 5 nights between 1899 and 1903. The Santa Barbara Independent proclaimed,

“There is only one Zamloch in the world – men of such marvelous skill have never been plentiful…we expect to see the beautiful Opera House completely filled with the most jolly set of people ever assembled in this city. Many valuable presents will be distributed this evening and we are sure everyone will be pleased and more than pleased.”

While we wait in the wings for things to return to normal, we hope you enjoy a peek into the Lobero archives.

We hope you’re staying safe and enjoying the arts from the comfort of your own home. Go ahead and read more stories below.