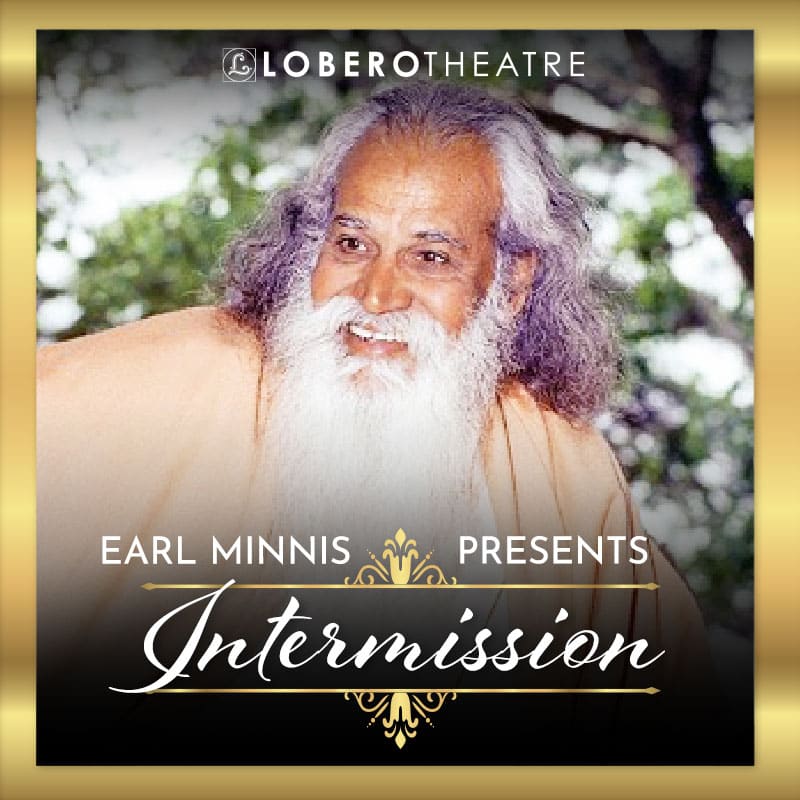

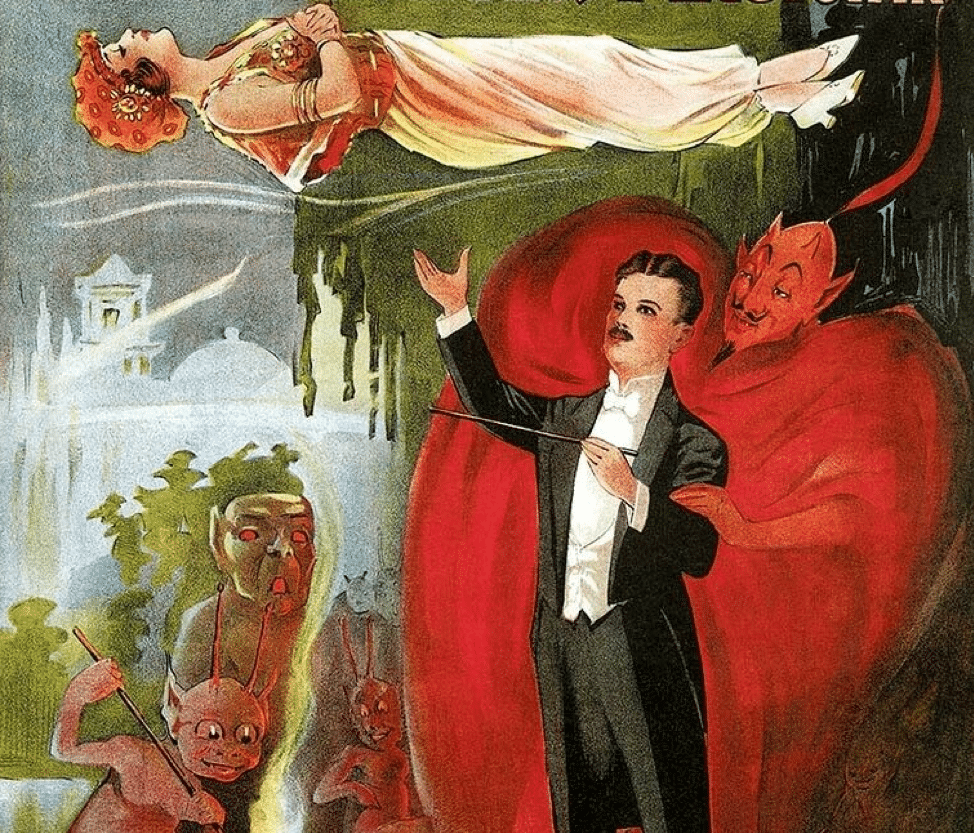

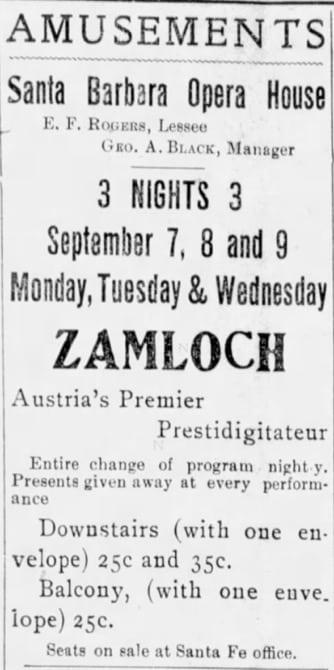

The Lobero Theatre has seen many colorful and memorable performances in its 148-year history. But arguably the most bizarre took place over three days beginning on January 13, 1896 – when the “Boy Wizard” commanded the stage footlights.

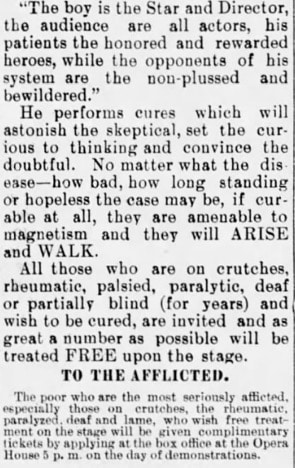

No, not a 19th-century predecessor of Harry Potter, but instead the “world’s invincible magnetic healer who cures the deaf, blind, sick, lame, rheumatic and paralytic by the laying on of hands.”

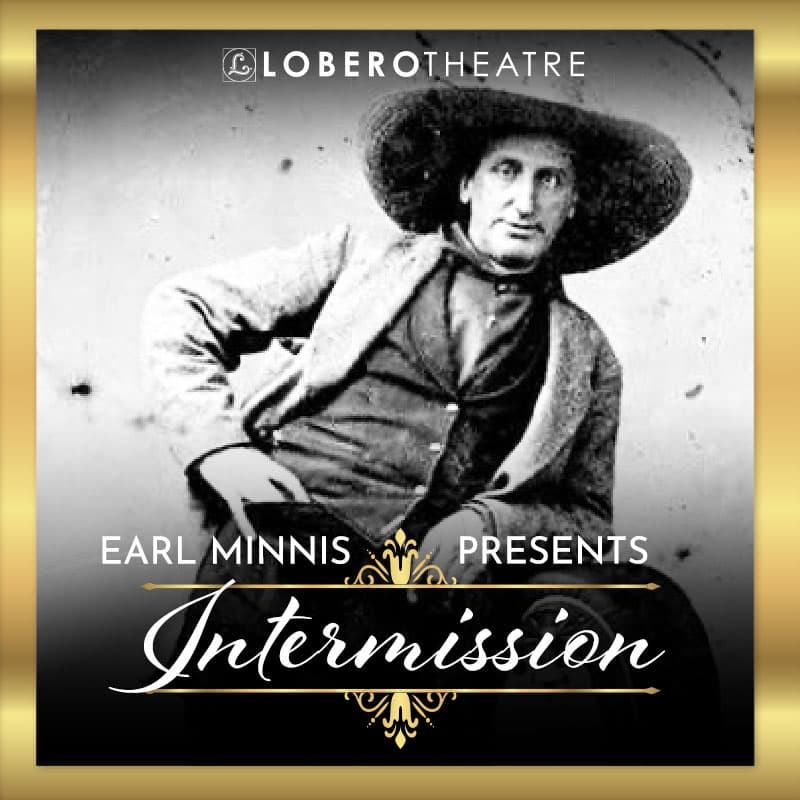

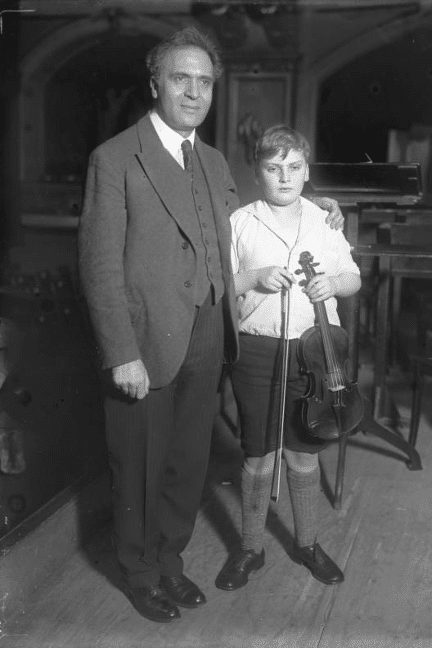

The Boy Wizard was a young German named Karl Herrmann. He had been discovered by W. Fletcher Hall, an American promoter and self-proclaimed health professor. Prof. Hall had made a career of managing “magnetic healers” and just a couple of years earlier had toured with a young man he had dubbed the “Boy Phenomenon.” But in 1895 the two had a falling out, and the Boy Phenomenon was quickly replaced by the Boy Wizard, who Hall proclaimed “daily generates ten times more magnetism than the former Phenomenon.”

In the late 1800s the lines between science and pseudo-science were not clearly drawn, and medicine was a curious mixture of science, home remedies, and outright quackery. In 1896, newspapers like the Santa Barbara Press and the Daily Independent were filled with ads for cure-all tonics and lotions.

The theory of “animal magnetism” originated with a German doctor named Franz Mesmer in 1779. Mesmer proposed that there was a magnetized liquid inside all living things – including humans – which was the key to physical and psychological health. While the magnetic fluid was “subtle” and couldn’t be extracted or studied, Mesmer believed that fluid imbalances and blockages were the cause of illness. He trained practitioners who could supposedly move the fluid by massage or by making sweeping movements of the hands over the patient’s body. While being treated, patients were said to be “mesmerized” – going into a kind of waking sleep or trance – which later became known as “hypnosis.”

Mesmer’s theory was controversial even in its time, as National Geographic explains, “In August 1784 King Louis XVI (whose wife, Marie-Antoinette, was a patient of Mesmer) ordered a commission to evaluate Mesmer and his treatment methods. The nine-member committee—which included American inventor and statesman Benjamin Franklin…concluded that Mesmer’s theory of animal magnetism was ‘destitute of foundation,’ as it was impossible to prove the existence of a fluid that lacked taste, color, or scent. When the commission’s report was published, Mesmer lost much of the public’s support and became the scorned subject of satires. He left Paris, living in relative obscurity until his death in 1815.”

Modern science has found no evidence to support the theory of animal magnetism, and it has long been regarded as one of history’s most colorful debunked medical theories – along with blood humours (and bloodletting), and female hysteria.

But did mesmerism work? The answer seems to be that for some people, there indeed were short-term benefits. “There are many semi-documented cases (mostly by Mesmer himself) of patients who seemed to recover after receiving mesmeric treatments. However, science-minded individuals at the time and in the centuries since have suggested that any positive effects from his services should be credited not to magnetism but rather to psychological means, i.e. psychosomatic healing through the power of suggestion.”

Modern science has found that hypnotism can be beneficial for some health conditions such as pain relief, GI ailments like irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), tension headaches, and mental health issues like anxiety and depression.

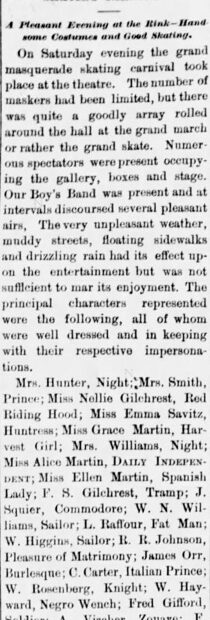

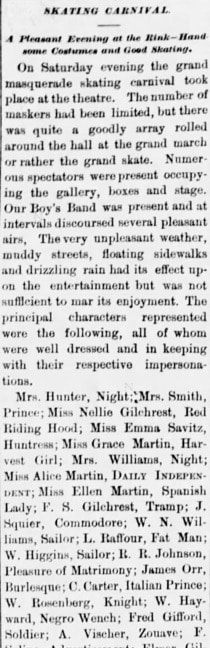

And what about the Boy Wizard? His three performances at the Lobero Opera House in 1896 received glowing reviews from the Santa Barbara Independent.

“People who were known by the audience to be dependent on crutches for many years were made to walk across the stage with ease and vigor. James Andrews, who has for years been the subject of serious hip disease, and who could hardly walk with crutches, was after a moment’s treatment, not only able to walk but to walk up and down the aisle with his crutches on his shoulders. To epitomize the performance, the deaf heard, the lame walked, the paralytic scampered around, and the audience greatly enjoyed itself.”

A key element of Prof. Hall’s tour with the Boy Wizard was booking a room at a local hotel and charging clients for personal healing visits. A personal consult with the Boy Wizard cost $1.00 ($30.00 in 2021 purchasing power). Business in Santa Barbara was so brisk that he stayed for 2 weeks at the San Marcos Hotel after his Lobero appearance.

After their Lobero run, Prof. Hall and the Boy Wizard spent 3 months performing in Los Angeles, and elicited wondrous (and preposterous) newspaper headlines in the Los Angeles Times –

Cures Performed By The Boy Wizard That Rival Those Of 1800 Years Ago

Cured By The Boy Wizard Who Daily Generates An Inexhaustible Supply Of Vital Magnetism

Will Appear In His Godlike Work Of Healing The Sick And Curing All Manner Of Chronic Ailments

But then all the wizardry came crashing down. In March 1896, the Boy Phenomenon sued the Boy Wizard and Prof. Hall for tarnishing his career and for using the same testimonials in advertising. The suit claimed that the Boy Wizard was pocketing $300,000 a month (in today’s money). In July 1896 the Boy Wizard was accused by the state of Washington of practicing medicine without a license and in September Hall and Herrmann absconded to Hawaii, and then to Australia.

Sources

- https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/68420/what-animal-magnetism

- https://www.esalen.org/ctr-archive/animal_magnetism.html

- https://insroland.org/category/electomagnetism/

- https://www.encyclopedia.com/social-sciences/culture-magazines/1900s-medicine-and-health-overview

- https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/magazine/2019/03-04/franz-mesmer-hypnotism-mesmerized/

- https://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org/article/S0025-6196%2811%2963203-5/fulltext

- https://www.newspapers.com/