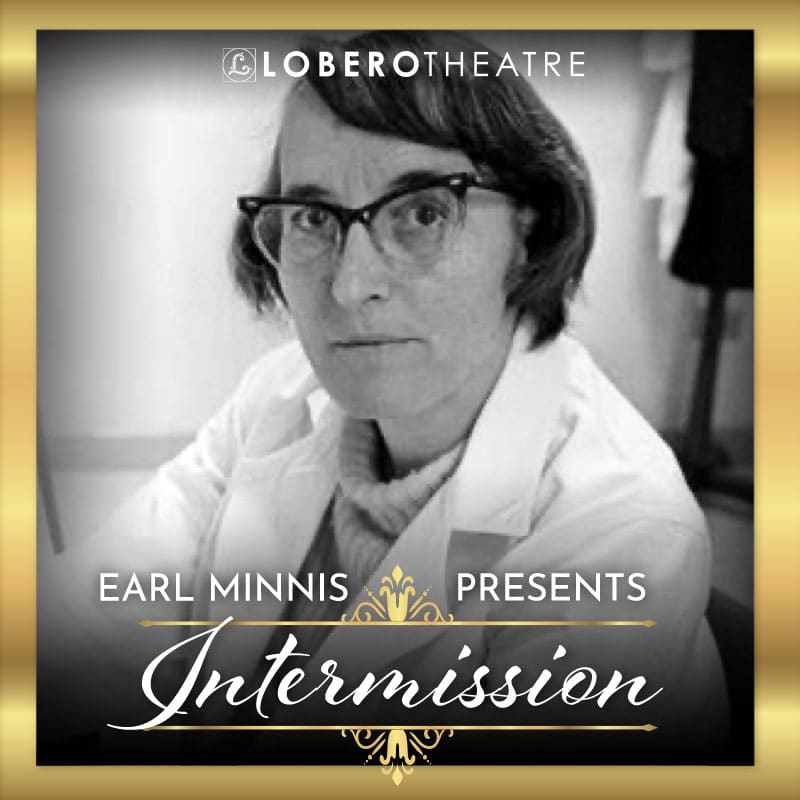

On the evening of October 4, 1977, a petite woman with a Swiss-German accent held a standing-room-only Lobero audience spellbound as she spoke about what she called the greatest mystery in science – death.

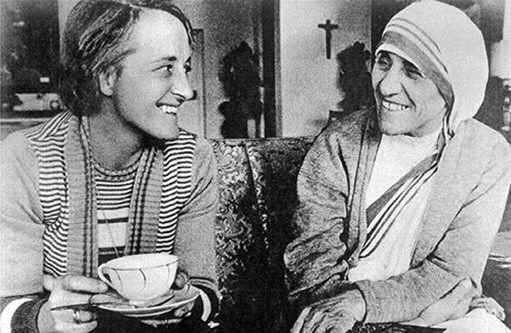

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross could joke about being the “death-and-dying lady,” but her pioneering work in changing the way Western culture dealt with death, dying and bereavement made her one of the most important thinkers of the 20th century.

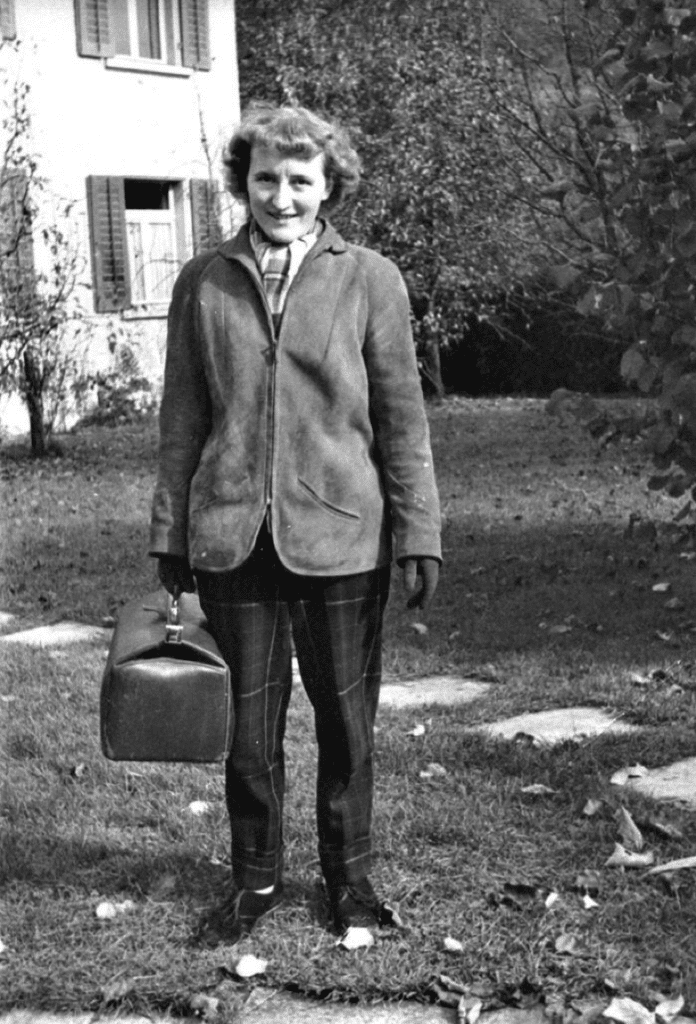

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross was born in Zurich, Switzerland in 1926. The first of triplets, Kübler-Ross weighed only two pounds at birth and was not expected to live. By the sixth grade, she announced to her parents that she wanted to be a doctor, and at the age of 16 – and defying her parents – Kübler-Ross left home and volunteered at the largest hospital in Zurich to help refugees from Nazi Germany.

When World War II ended, Kübler-Ross joined the International Voluntary Service for Peace, a European organization that served as the model for the Peace Corps, and she was one of the first outsiders to visit the Maidanek concentration camp in Poland. There she found the walls covered with drawings of butterflies, scratched by children who were about to be sent to the gas chambers. It was at Maidanek, she later wrote, “in the midst of suffering that I found my goal.”

Returning to Switzerland, Kübler-Ross earned her medical degree at the University of Zurich, and met Emanuel Ross, an American doctor. They married in 1958 and moved to New York, where she completed her psychiatric residency. In 1962, Kübler-Ross was a teaching fellow at the University of Colorado School of Medicine and was shocked by the way the hospitals she worked in dealing with dying patients. “Everything was huge and very depersonalized, very technical,” she told the BBC in a 1983 interview. “Patients who were terminally ill were literally left alone, nobody talked to them.” In response to what she felt was an unhealthy approach to death and dying, Kübler-Ross started a seminar for medical students where she interviewed people with terminal diagnoses and asked them to talk about how they felt about death. Although she met with stiff resistance from other physicians, the seminars were soon standing room only.

In 1969, Kübler-Ross wrote a book called On Death and Dying. In it, she described how patients talk about dying and discussed how end-of-life care could be improved. The most publicized part of the book was Kübler-Ross’ description of 5 common emotional stages to dying: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. While the public, and even surprisingly the medical establishment, responded enthusiastically to the “5 Stages of Dying,” Kübler-Ross felt most took it too literally. According to the New York Times, “Not all dying patients follow the same progression, Dr. Kübler-Ross said, but most experience two or more stages. Moreover, she found, people who are experiencing traumatic life changes like divorces often experience similar stages. Another conclusion she reached was that the acceptance of death came most easily for people who could look back and feel that they had not wasted their lives.”

By 1972, Kübler-Ross was frustrated by the way her research had been misinterpreted by her medical colleagues and decided to devote herself full-time to lecturing and teaching a seminar called “Life, Death, and Transition.” Unfortunately, it was also at this time that Kübler-Ross’ professional reputation began to decline when she expanded her work on end-of-life care into theories about what happens after death and started researching near-death experiences and spirit mediums. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, her lectures – including the two she gave at the Lobero Theatre – were evenly divided between her groundbreaking work on death-and-dying and the hospice movement and spiritualism.

As explained by the New York Times,

“In 1976, she fell under the sway of Jay Barham, a former Arkansas sharecropper who had founded the Church of the Facet of Divinity and said he was able to channel spirits and communicate with them. Dr. Kübler-Ross talked about setting up a worldwide network of franchised centers with him and his wife to counsel on the problems of dying and living. His program was investigated by the San Diego district attorney’s office because of accusations of sexual misbehavior. She severed ties with him, and years later acknowledged that she had been mistaken about him and that he had deceived many people.”

In the 1990s, Kübler-Ross suffered a series of debilitating strokes and moved into a hospice. She died on August 24, 2004, of natural causes, surrounded by friends and family. Not long before her death, she had finished work on her 20th and final book, On Grief and Grieving.

Sources:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elisabeth_K%C3%BCbler-Ross

- https://www.nytimes.com/2004/08/26/us/elisabeth-kubler-ross-78-dies-psychiatrist-revolutionized-care-terminally-ill.html

- https://www.bbc.com/news/stories-53267505

- https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/1470196/Elisabeth-Kubler-Ross.html

- https://www.economist.com/obituary/2004/09/02/elisabeth-kubler-ross